The definitive bitcoin IRA handbook

The security of the bitcoin protocol has an unmatched track record spanning more than 15 years, convincing even the largest institutions to entrust it with treasuries worth billions of dollars. If you hold bitcoin or are considering doing so, this knowledge can be comforting. But on the other hand, it’s not uncommon to feel uneasy and question how a dozen words or a short string of address characters can be resilient against the most sophisticated attackers or future technological developments.

In this article, we’ll run the numbers and explore the basic cryptographic mechanisms that underpin a bitcoin wallet’s security. By the end, you’ll be in a better position to understand how the bitcoin protocol offers you sufficient protection and security for your long-term savings.

The durability of the bitcoin protocol is not accidental. At its core, bitcoin’s security stems from mathematical principles. It’s based on a security model built upon decades of cryptographic research, designed to resist brute force, mathematical breakthroughs, and adversarial attacks. To understand how this all comes together, we’ll explore the tools that make it possible: secure entropy, hash functions, and asymmetric cryptography. Once we understand these building blocks, we can revisit how bitcoin utilizes them to achieve its remarkable security.

Entropy is the starting point for most secure systems. It can be thought of as a fancy word for randomness, the kind that shows up in the tiny wobble of a coin toss, the exact timing of your keystrokes, or the jitter of electronic noise inside a device. It is a measure of unpredictability in a system, characterized by the absence of a clear pattern, and what makes certain events impossible to forecast with certainty.

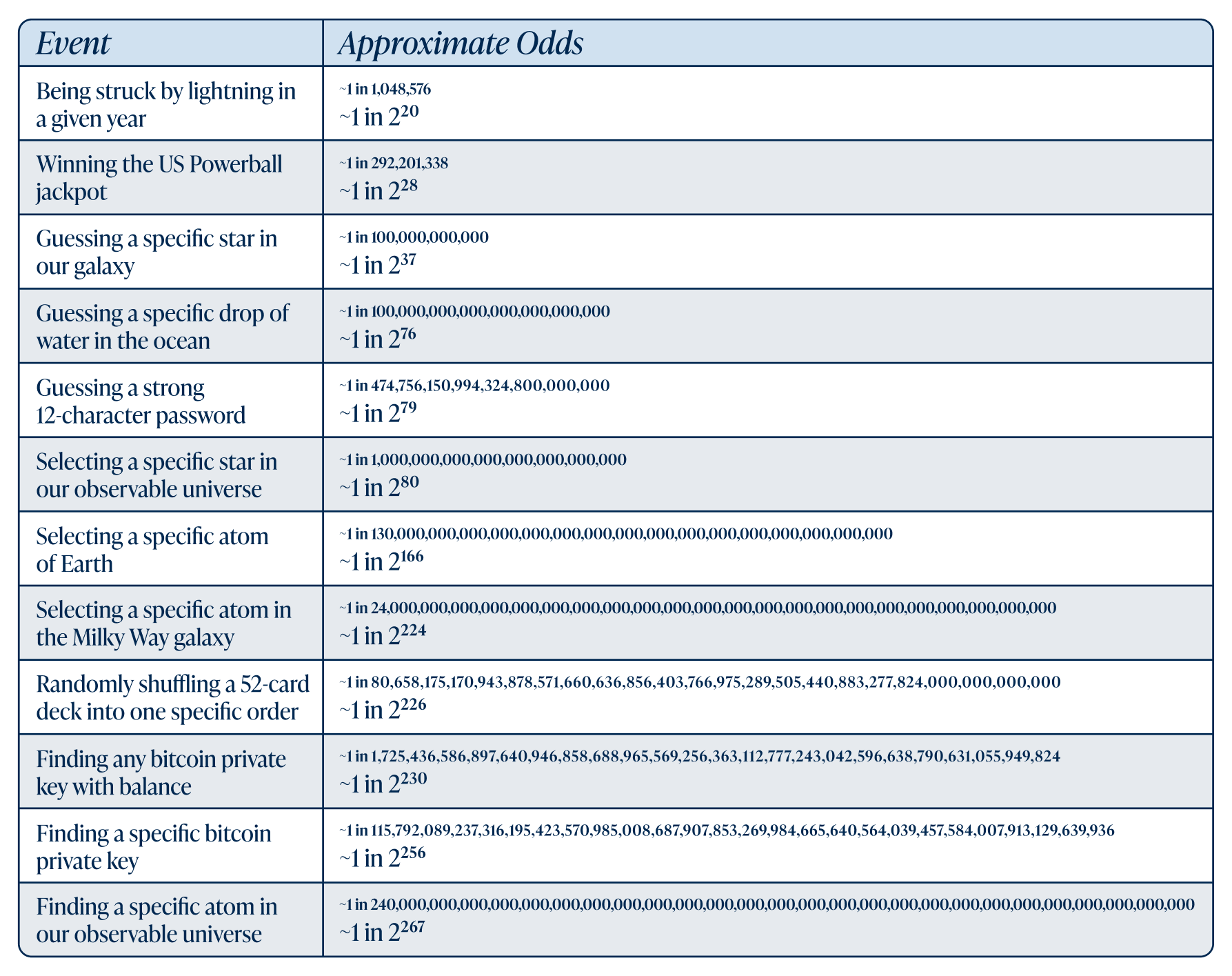

In cryptography, that same unpredictability is used to generate secure numbers—values so large and random that even the most powerful supercomputer couldn’t hope to recreate them. The space of possible outcomes is astronomical. To give a sense of scale, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) considers roughly 2¹¹² possible combinations (also known as 112 bits) as the lower bound of what is considered sufficiently random for a secure number. NIST standards guide governments, developers, and security engineers toward algorithms that are efficient and resistant to attacks. Modern cryptographic systems, including those used in bitcoin, go far beyond this threshold.

For comparison, it helps to translate these abstract probabilities into a specific time frame. Even when using modern hardware, the growth of the search space quickly outpaces any realistic computational capability. A current consumer-grade MacBook Pro can exhaust a space of roughly 220 possibilities in milliseconds and 227-228 possibilities in under a second. But with each additional bit of entropy, the work required doubles in magnitude.

If you used a MacBook Pro to search for a specific star in our galaxy, about 237 possible targets, you would need only a few minutes. Attempting the same brute-force search across the entire known universe, which would involve roughly 280 possibilities, would instead take over 71 million years. Beyond that point, the numbers quickly move outside any human or technological timescale. Even if every computer on Earth were guessing trillions of values per second since the Big Bang, the vastness of the search space for most cryptographic secrets (2256) would remain effectively untouched.

Because these numbers are generated from true randomness rather than predictable patterns, an attacker can not reverse-engineer them. They can only attempt blind guesses in a space so vast that success is practically impossible. Entropy, in short, provides genuine unpredictability; the foundation upon which all modern cryptographic security is built.

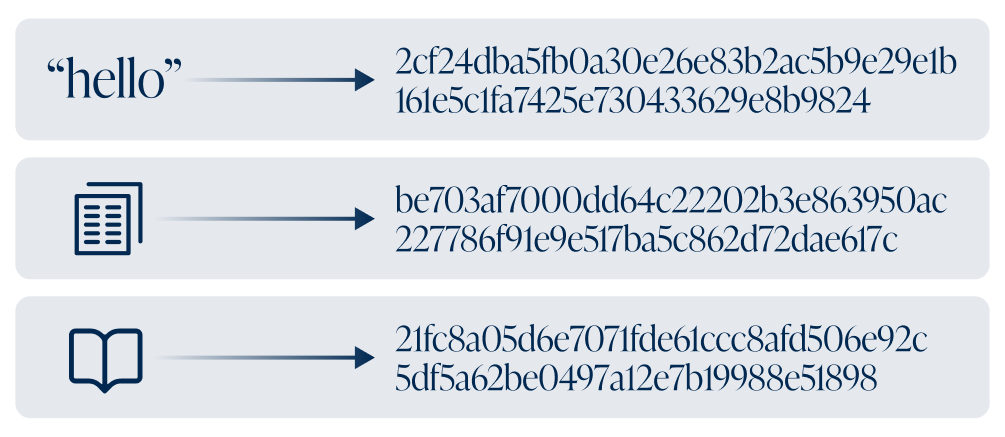

A hash function is a mathematical one-way street. You can feed it any input (also called a “preimage”), whether that’s a single letter, a paragraph, or the entire contents of your favorite book, and it returns an output in the form of a fixed-length string of numbers and letters, called a “hash.”

Hashing only works in one direction. It’s easy to input data and get an output, but given just the output, it’s practically impossible to figure out the original input. Of equal importance, even the slightest change to an input completely changes the output. While it is theoretically possible for two different inputs to produce the same output, a rare event known as a collision, a hash function with a large enough output space makes such collisions practically impossible for the same reasons discussed in the entropy section above. For example, SHA-256, part of the Secure Hash Algorithm family standardized by the NIST, produces a 256-bit result. That’s 2256 possible outputs, comparable to the number of atoms in the observable universe (about 2266), making collisions effectively impossible even for the most sophisticated computers today. In practice, this means each hash can serve as a unique identifier for its original data.

Hash functions quietly protect much of our digital world. Software downloads use hashes to confirm integrity. Online services store passwords as hashes to maintain their security. Email and cloud systems employ them to detect duplicates. And digital signatures, certificates, and version-control systems rely on them to prove authenticity and track changes immutably. We can think of hashes as a fingerprint for data, being short, unique, and tamper-evident. But unlike human fingerprints, which can sometimes be faked or misread, cryptographic hashes are mathematically guaranteed to be unique for all practical purposes.

Hash functions are secure not because no one has tried to break them, but because even the fastest computers would need longer than the universe has existed to do so. Their strength lies in both design and output size.

Asymmetric cryptography, also known as public-key cryptography, enables two parties to communicate securely or verify authenticity without sharing a secret in advance.

This system operates with a pair of cryptographic keys: one public and one private. The private key is secret and never shared, while the public key is safe to share with other people. With the private key, you can create a digital signature. With the public key, anyone can check that the signature is valid. The important part is that the public key can confirm the authenticity of the signature without the private key itself ever being revealed.

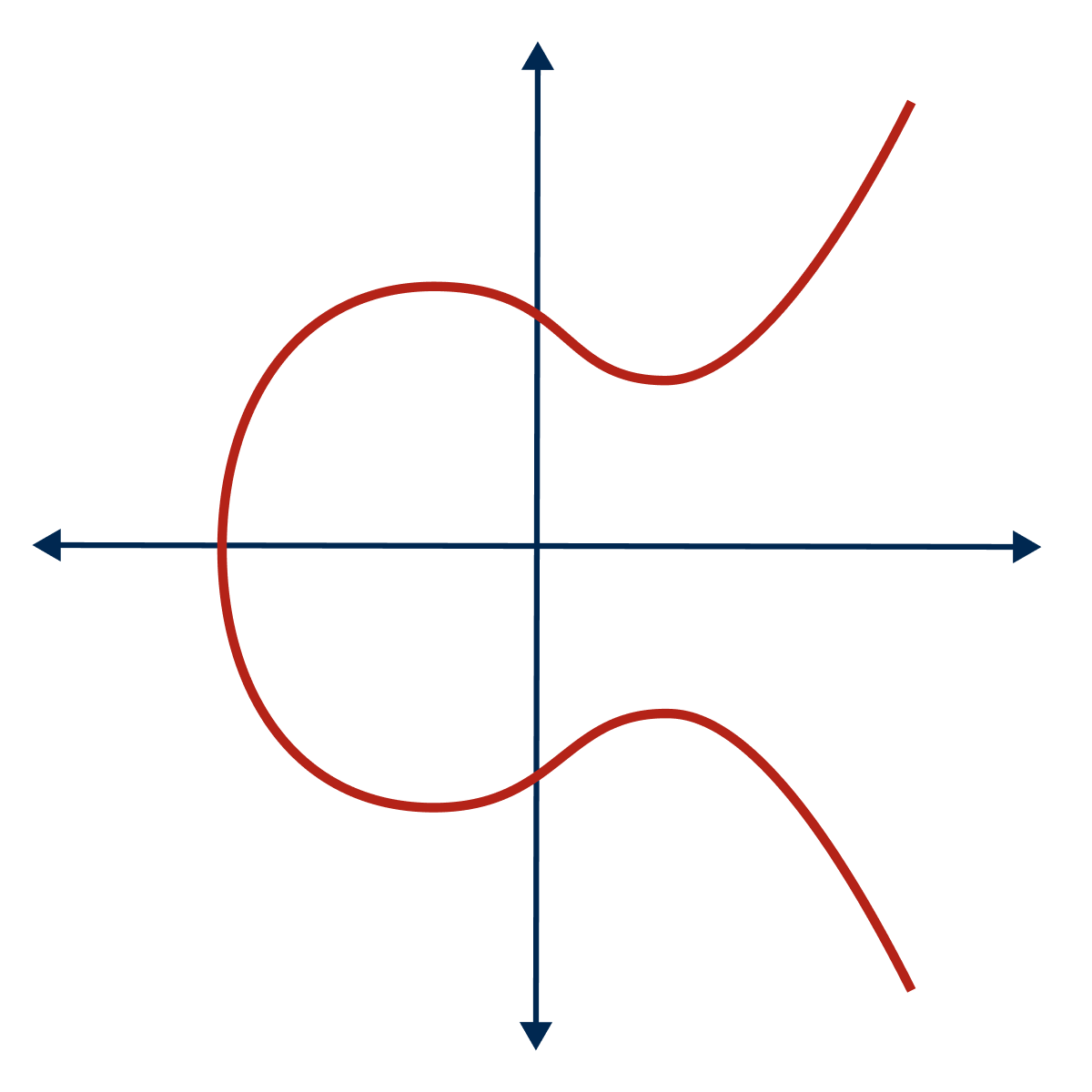

Asymmetric cryptography depends on computations that are easy in one direction but practically impossible to reverse. These one-way functions make it feasible to create a key pair, but infeasible for anyone to derive the private key from the public one. Among several asymmetric cryptography systems, elliptic curve cryptography (or “ECC”) has become one of the modern standards, as pointed out by NIST. While earlier systems such as RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) remain in use, ECC offers high-level security with significantly smaller key sizes. This makes it more efficient for modern applications, from mobile devices to core internet infrastructure.

Elliptic curve cryptography is based on the mathematics of points on an elliptic curve defined by an equation such as y² = x³ + ax + b. In simple terms, the curve’s geometry allows for complex mathematical operations that are quick to perform in one direction but effectively impossible to undo without knowing a secret number.

Like other cryptographic systems, its security ultimately depends on numbers so large that guessing a private key or signature is virtually impossible. The key space must be vast enough that two private keys producing the same public key, a collision in the key generation process, will not happen. As mentioned, current standards consider 2112 possible combinations as the lower bound for acceptable security, and well-designed systems, such as modern elliptic curve cryptography, exceed this by many orders of magnitude.

Asymmetric cryptography, and ECC in particular, forms the backbone of digital trust today. It secures web connections (like HTTPS), authenticates software updates, enables digital signatures, and powers end-to-end encrypted communication. Whenever your browser locks onto a secure website, or your phone verifies an app’s authenticity, it’s asymmetric cryptography at work, turning abstract mathematics into everyday digital security.

Now that we understand the primary security tools and the minimum thresholds required for adequate protection, we can examine the bitcoin protocol specifically and analyze the mechanisms it relies on to achieve its security.

When you create a bitcoin wallet, the very first step is generating entropy, the raw randomness that ultimately becomes your private key. Your seed phrase—those 12 or 24 words written on paper or stamped into metal—is simply a human-friendly translation of that entropy which is initially expressed as binary bits.

This entropy can come from multiple sources. It may be supplied by your computer's operating system, by specialized hardware wallets that follow established randomness standards, or even by simple physical processes like rolling dice, flipping coins, or shuffling cards. Regardless of its origin, the goal is always the same: to produce unpredictable bits of randomness that exceed the minimum security threshold.

As discussed above, acceptable cryptographic security begins at about 112 bits. Bitcoin goes well beyond that. A 12-word seed phrase represents 128 bits of entropy, and a 24-word seed phrase represents 256 bits. Both are far above the 112-bit minimum, and even 128 bits is more than 65,000 times stronger than that baseline. This enormous security margin is what makes private keys derived from correctly generated seed phrases effectively unguessable, even with the most powerful computers imaginable.

To understand where these numbers come from, each seed phrase word carries 11 bits of information. That means 12 words add up to 132 bits. However, a few of those bits are reserved for a built-in error-checking feature called a checksum (derived from hashing the underlying entropy), which reduces the true entropy to 128 bits. The same logic applies to 24 words, with 256 bits of actual entropy and the rest allocated to the checksum.

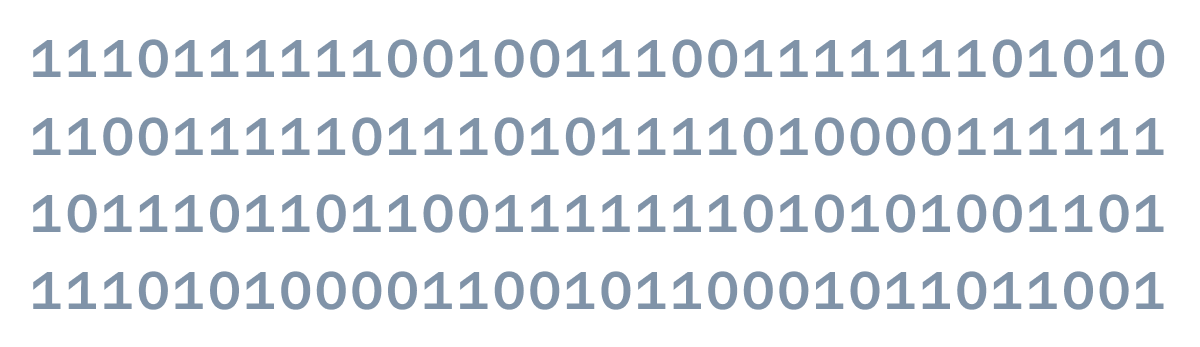

If you were to generate this entropy for your seed phrase using coin flips, each flip would produce one bit (heads = 0, tails = 1). A 12-word seed phrase would therefore require 128 flips; once entropy is accounted for, we would have a binary number that looks like this:

This is also where bitcoin’s model differs sharply from traditional finance. In traditional systems, security relies on human authentication and institutional oversight: passwords, PINs, two-factor authentication, and centralized encryption. Even when these are strong, an 8 to 12 character randomly generated banking password might offer around 276 possible combinations; it is still trillions of times weaker than the entropy in a 12-word seed phrase. A full debit card (its number, CVV, and expiry) offers roughly 250 combinations, which sits orders of magnitude below cryptographic standards. Unlike bitcoin, the ultimate control of those credentials lies with the bank, not the user, and comes with operational risks such as freezes, holds, or institutional mismanagement.

Bitcoin hardware wallets generate entropy using algorithms designed specifically for secure randomness. Modern devices utilize true random number generators (TRNGs) within secure elements or microcontrollers for generating entropy. Guidance from standards, such as those published by NIST, helps inform how entropy should be sourced, and many hardware wallets reference such frameworks or comparable security principles.

For example, Coldcard gathers entropy for your seed from several places. It utilizes the TRNG built into its main chip, but also draws on analog noise and can optionally incorporate a software PRNG (pseudorandom number generator). It then runs this through SHA-256 to clean and strengthen the output. Ledger devices generate seed entropy using the TRNG inside a dedicated, tamper-resistant security chip. Trezor takes a different approach by combining two independent sources: the TRNG inside its microcontroller and additional entropy from the host computer.

Bitcoin addresses are the public-facing identifiers you provide when you want to receive bitcoin. They appear short and simple, but they are actually the result of multiple layers of hashing and encoding.

Most addresses are derived by hashing a public key twice: first with SHA-256, then with RIPEMD-160. The result is a 160-bit hash that serves as the core data used to generate the final encoded address. Their job is twofold: to make payments practical for us and to shield the cryptographic material of the public key from unnecessary exposure.

This construction is known as HASH160, and it’s important to understand what it provides. While SHA-256 is applied first, it does not increase the preimage resistance of the final result; the 160-bit RIPEMD-160 output determines the overall security. In practical terms, this means an attacker would still need to find a preimage in a 160-bit space, an astronomically large search problem with 2160 possibilities.

As we learned above, hash functions with sufficiently large numbers virtually do not produce the same output from different inputs, and these same preimage resistance principles extend to bitcoin address formats. Whether an address uses a 160-bit hash (like P2PKH or P2SH) or a 256-bit hash (like P2WSH), every format is designed so that two independent wallets cannot arrive at the same address.

There are a couple of exceptions worth noting. Pay-to-Public-Key (P2PK), used in the very early days of bitcoin, and Pay-to-Taproot (P2TR), introduced in 2021, don’t hide public keys behind a hash the way most modern address types do. Instead, they show the public key directly. That doesn’t make them unsafe; it just means their security relies directly on the strength of the underlying mathematics of elliptic curve cryptography, rather than getting that extra “hashing layer” other address types use.

When a public key is exposed, attackers do not need to attempt to brute-force all 2256 possibilities. The real target is solving the difficulty of the elliptic curve problem itself, and the best known method of attacking it—Pollard’s rho—still leaves you with a mind-boggling amount of work. Even with that shortcut, breaking a key would take on the order of 2128 operations, well above the 2112 security threshold, making the chance of compromise negligible in practice.

For the cryptographically inclined, one interesting edge case comes from script hash addresses, which are popular for multisig wallets. The older of the two address types, Pay-to-Script-Hash (P2SH), utilizes the HASH160 of a redeem script, rather than a single public key. In a collaborative multisig environment, if you are the first one to provide your public key for the redeem script, a malicious collaborative partner with enough time and energy could try a “birthday attack” by finding a script collision. A collision attack like this entails finding any two preimages with the same hash, rather than a preimage with a specific hash, reducing resistance from 160 bits to 80 bits. At the time of writing, this attack remains highly impractical and there have been no known occurrences, but it’s worth noting that 80 bits is below the recommended security level.

This is why the newer address type Pay-to-Witness-Script-Hash (P2WSH) avoids RIPEMD-160 and utilizes a full 256-bit hash. By making this adjustment, it is able to provide 128 bits of security against a theoretical birthday attack, which better aligns with the security standards used elsewhere in the bitcoin protocol. You can learn more about this in our article covering segwit.

Transactions themselves are not fragile—once signed by your private key, the details (transaction amounts and destinations) cannot be altered without invalidating the signature. The real security challenge is ensuring that the signed transactions are included in the blockchain and remain there.

This is where bitcoin’s proof of work comes in. Each block is secured by a proof-of-work requirement built on SHA-256, the same hash function family discussed earlier. Miners must repeatedly hash block data until they find an output below a specific target value. There’s no shortcut: the only way to find a valid hash is to spend computation and energy guessing trillions upon trillions of possibilities.

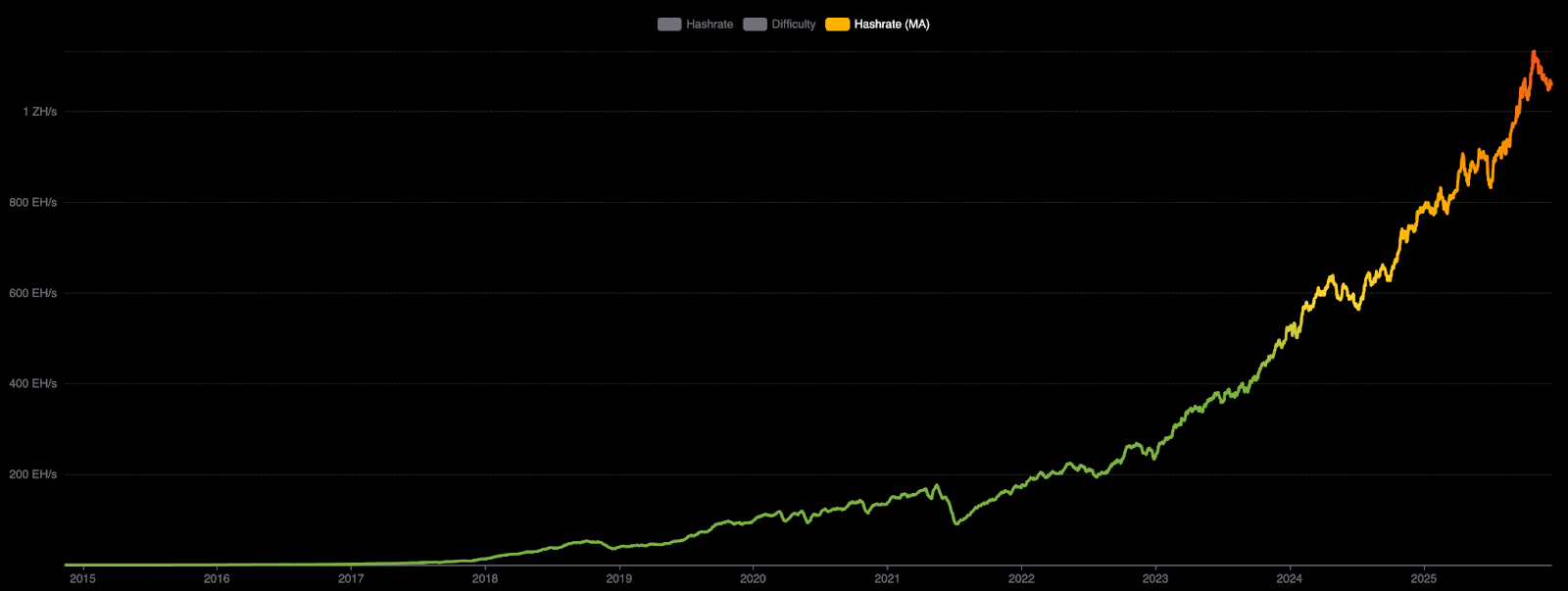

The difficulty adjustment is what keeps this game fair. Every two weeks, the network automatically recalibrates the target so that blocks continue to arrive about every 10 minutes, regardless of the amount of mining power joining the network. In effect, bitcoin’s security continually adjusts to match the mining power on the network, ensuring it always stays ahead of any potential attacker. At today’s difficulty levels, mining machines around the world collectively make guesses on the order of 279 possibilities every 10 minutes, a threshold that grows over time as more mining machines are introduced to the network.

In a theoretical “51% attack,” one entity controls the majority of the network’s mining power. Such an attacker couldn’t forge transactions or steal coins, but they could temporarily prevent certain transactions from being confirmed or even attempt to reverse their own payments. Pulling this off against the combined hash rate of the bitcoin network would require nation-state-level resources, and sustaining it long enough to profit is even more unlikely.

For ordinary users, the practical point is this: once a transaction has several confirmations, it is effectively irreversible, secured by the largest and most energy-intensive computer network in the world.

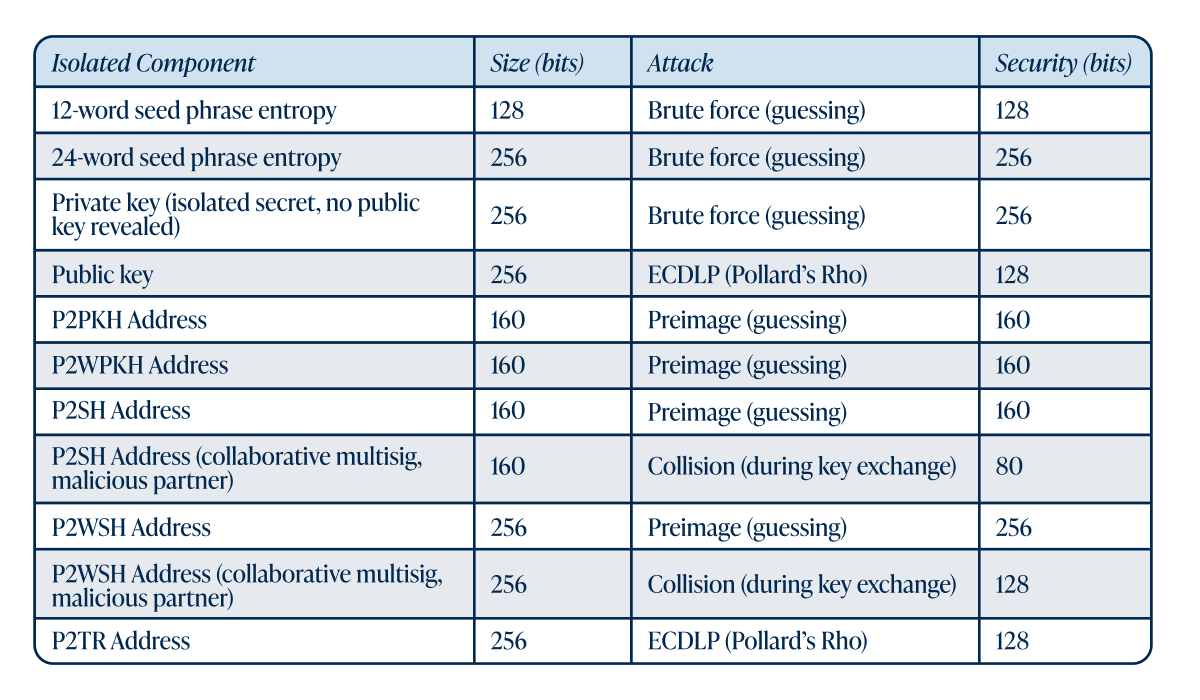

To tie all these concepts together, the chart below summarizes the “bits of security” behind the bitcoin protocol and its cryptographic tools.

As the chart illustrates, nearly every cryptographic component that underpins bitcoin's security sits comfortably above the 112-bit security threshold. The one outlier, a collision attack in collaborative P2SH multisig setups which we discussed above, is why newer constructions within P2WSH were introduced. It's important to remember that while 256 bits is mathematically larger than 160 or 128 bits, all three represent search spaces that are beyond the reach of any conceivable attacker. Moving from 128 to 256 bits merely adjusts the search space from "practically impossible" to "also practically impossible."

Bitcoin’s security is built on layers: entropy makes private keys unpredictable, hash functions preserve integrity, elliptic curve cryptography ties ownership to your private key, and proof of work engraves transactions into an immutable chain. Together, these defenses have held firm for more than 15 years against every class of attack and continue to grow stronger. What begins as a string of random bits or a handful of words on paper ultimately becomes a system that rivals and surpasses the security standards of governments, banks, and major technology firms. In the end, bitcoin’s strength comes from proven cryptography paired with extremely large numbers. As time passes and new technological advancements surface, bitcoin can be upgraded to meet the new security parameters, just like any other technical system.

Understanding that the bitcoin protocol exceeds modern security standards isn't always enough to feel comfortable managing your own self-custody wallet—for most people, the real challenge isn't grasping the underlying math, but ensuring that security is implemented correctly and consistently in day-to-day custody. That's why Unchained offers collaborative multisig vaults, where you hold the controlling keys but also have professionals on standby to provide education and technical assistance. Collaborative custody bridges the gap, allowing you to rely on bitcoin's foundations without having to manage technical decisions in isolation. Book a free consultation now and know we're here to help every step of the way!